"How is it that in Ameriki it is morning, while it is afternoon here?" says my neighbor Musa, stretched out in a hammock, shaded from the scorching sun by a hangar of dried straw.

"Well..." I stumble, trying to buy time as I grasp for words like "orbit, time zone, and rotatation" in my limited Bambara vocabulary

"Yeah," adds his friend Nanturu, "And why does Ameriki have more than one time?"

I glance over at a pile of squash and pick up the roundest one I can find.

"This is the Earth." I point to the stem, "and this is Mali," then I slowly rotate it and point to the other side, "here is Ameriki."

I've been thinking a lot in the past few months; take away all my distractions (like a job, a road bike) and plunk me into an animist farming village, and that's likely to happen. I read a lot, I write a lot, and I have developed the ability to pass several hours at a time staring off into space thinking about things while I sit with a group of Malians speaking Senufo to each other. My thinking sessions are sometimes spiced up with conversation, and nearly always punctuated with the three rounds of tea, boiled in little blue pots on charcoal stoves, served in shot glasses with lots of foam.

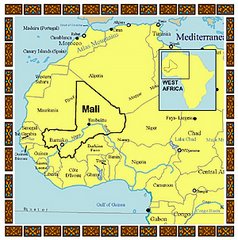

So on this scorching afternoon, as I suck the last foam bubbles from my glass, I think about Galileo. He had this whole "earth going around the sun" thing figured out a really long time ago. Western civilization figured out a lot of things a long time ago - mathematics, calculus, physics, the whole concept of scientific inquiry, and a system of writing to write all this stuff down and share the knowledge acquired, literature, political systems and philosophy, theater, photography. My mind starts reeling and I blink a few times. A guy roars into the hangar on a Yamaha motorcycle. The faded, gangsta-rapper face of 50 Cent grins from his t-shirt, framed by the words "Get Rich or Die Trying." The layers of irony are almost too much for me to handle. How the world market brings in He greets in crisp Bambara, and I immediately peg him as a rich city slicker from Sikasso (yes, I stereotype non-villagers now). He adds a liter or two of crude oil to his tank and drives off. I think about African American poverty and how different it is from African poverty; I think about why people would (and do) die to get rich, I think about how the t-shirt was donated and shipped across the ocean to end up in the used clothes piles all over Africa. After my diversion, my thoughts return to Galileo. Why did the West develop all those things while African countries did not? Why? I've read Guns, Germs and Steel and I know that the answer is complicated; related to the unfair North-South continental axis that prevents the spread of innovation. I also know that without a food surplus created by efficient agriculture, people can't liberate labor to start doing other things (like sitting around thinking), which lead to what we call development and progress. With thoughts like this, I start to appreciate the value of my role as an agricultural extension agent.

I started holding meetings with my villagers to get to know their agricultural work; to know what they grow, how they grow it, and what problems they encounter. The soil is overworked and eroded, they have no equipment, no irrigation, no knowledge of pest management, and a fuelwood demand that leads the women out for hours in search of wood. To feed their families, they grow millet, sorghum and corn to fill round mud granaries. For "cash," they grow tiger nuts (a ground nut like peanuts, only sweet!) and cotton, neither of which actually bring them cash after they pay back the loans they take for fertilizer. And without equipment, without soil conservation practices, without cheap transport to markets that will buy their goods for a fair price, each year gets harder...and it is difficult to know where to begin.

To stimulate my thinking, I've been reading. Luckily, a series of incidents bestowed me with copious amounts of time to do this. Three weeks ago I started getting high afternoon fevers, and after a few days of that the med office thought I might have malaria, so I hopped a bus into Bamako. At the same time I got an infection on my lip and it started to swell. By the time I got to Bamako my cyclical fevers were gone (I had taken the emergency anti-malarial meds), but my lip was the size of a golf ball. I spent more than a week drugged up, reading books, and thinking about what it would be like to be deformed. I got to know what it feels like to be stared at, to having people ask me "What's wrong with your face?" I wondered what it would be like to have a permanent deformity. It finally pussed out of my lip and I returned to normal.

Only a week after getting back from Bamako I rode my bike into Sikasso to do some research on agriculture NGOs in my area. Walking through market, I got hit by a motorcycle - it knocked me over and then ran over my foot, taking a good chunk of my skin with it. I then spent a week with an infected foot, sitting in my hut boiling water to clean it and soak it.

I read Into the Wild, about a young man who leaves society to live on his own in the wilderness. It made me think about my own desire to see how humans can live with/in/against nature. In the West we have developed so much that we are starting to lose touch with our roots, so to speak. We don't know what it is like to grow our own food and wait for the rains to come. We don't kill our own animals, we don't wake up with the sun and go to bed with it. It's almost like we live outside nature - insulated by our walls and clothes and cars and electricity. There are a few of us who desire to get outside the insulation. We do it through backpacking, trips into wild places, and also through things like what I'm doing right now: living in a society that lives closer to nature. I get my water at the well, I write in my journal by lamplight, and I eat food that was grown less than a mile from my house. Funny thing is, the people here have an opposite desire. I can't tell you how many times I have heard "Ameriki is rich. Take me with you to Ameriki." I grope for words and mumble something about visas. I want to take off my watch and my sunglasses and hide my bicycle in a bush so they are not forced to see these signs of wealth that they don't have access to, and that perhaps they do not need.

This past week a gaggle of Peace Corps volunteers convened in Sikasso to celebrate Thanksgiving. We divided into teams- the turkey team (they made aprons), the stuffing team, the pie team, and cooked a feast beyond comparison. It was wonderful to be among friends, to be able to speak and express myself, to hear stories from my fellow volunteers. It takes time apart from something to truly appreciate it. Here's my thanksgiving toast: to friends.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Jessie this is amazing writing, and you look to be having an awesome time. I am so impressed by you! Your entries are suffused by a sense of peace and calmness, even when being hit by a motorcycle (!). You amaze me.

Hey Jessie, just letting you know I think your work is inspirational. I've had a growing interest in discovering what world poverty is really about in the past few months, and your insight is invaluable. I started reading The End of Poverty by Jeffrey Sachs, which I highly recommend as it outlines the current dire situations of many of the world's impoverished economies and what he believes to be the legitimate solution to eliminating extreme poverty by 2025. I plan on reading Guns Germs and Steel afterwards, as I've heard it's a phenomenal book. Anyway, I'm a big fan of yours, and I'm proud of being your friend. Good luck, and keep the blogs coming!

Post a Comment