Most of us like to get a tester spoon of that chocolate hazelnut gelato before we buy it; to run the flavor over the tongue and decide yes, I do in fact want to invest in a more prolonged experience. The Peace Corps apparently recognizes this human tendency and sent all the trainees to our real sites this past week to get a sample of where we will be living for the next two years of our lives.

So last Tuesday I met with Abdouleye, a farmer from my region who will serve as my "homologue," a go-to-person and guide to help me work in agriculture in my region. He is a slight man with a furrowed brow that quickly flattens into a grin. We went to the bus station together and sat on some old crates to wait a few hours for the bus to fill. The bus station swarms with men and women balancing huge baskets and platters of fried cakes, bananas, toothpaste, jewelry and radios, all teetering with impossible grace on the tops of their heads. Finally the bus "boiled" (Bambara is a language that I have dubbed a "homonymic whirlpool" because each word has twenty meanings. The word wuli means to plow a field, to boil water, to stand up, to wake up, and for a bus to leave), and we sat in cramped seats, sweating in the stagnant air for seven hours until we reached our village in the South East of Mali: M'Pedougou.

M'Pedougou is a village of about 650 people of the Senufo ethnic group, situated on a main road; straddling the vein of modernity but still firmly rooted in tradition. When I arrived, I met my host family, Jakilia Bengaly and his three wives, beautiful people with big white smiles and thick Senufo accents that I don't understand. They gave me my new name: Sita Bengaly, and we sat out by the roadside in front of Jakilia's little butiki (store). Next they took me to my house, weaving through the village on a little path past thatched huts and gardens and big trees. There was my house on the edge of town: a mud brick cottage with a thatched structure outside for shade. Big vines and flowers fill my yard, and I plunked down in my hammock, realizing that this is my new HOME. I went to the pump and got water, set up my mosquito net, and went to meander in the village.

It turns out that well, Senufo people speak Senufo. Most of them have learned Bambara as a second language, but they speak Senufo amongst themselves and when given the choice. I spent a good portion of my week in village sitting around listening to the crazy sounds of Senufo and wondering if I will ever be able to learn a language that sounds like Chinese, but that has no written materials for me to learn from. We'll see. I will try.

The majority of the villagers are subsistence farmers farming millet, sorghum, corn, okra and peanuts. My goal as a volunteer will be to help them develop better gardening and farming techniques, increased compost production, and to do what I can to enable them to improve their quality of life, in whatever capacity I can. At this point I still have no idea what I will be doing, concretely, when I get to village and have no structure, no "job," nothing but the sunrise and the sunset to structure my day around. It will be a radical change, that's what I do know.

Thursday, August 30, 2007

Wednesday, August 8, 2007

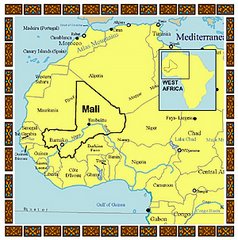

Malian artwork

Tuesday, August 7, 2007

Village life begins

Village life begins with the firing of rifles. When I arrive with four other volunteers at the end of a muddy road, the town elders come to greet us and fire shots into the air to announce our arrival. People emerge and line the path with color, music and smiles, handshakes and drumbeats. We wind our way into the heart of the village and gather around the grand tree, where we greet the chief and gave him a gift of kola nuts. Then the balafon players woo us into the center of the square and we dance, pulsing forward and backward in lines, women only, exchanging neck scarves, with hundreds of eyes fixed on our every move.

My host mother Kajatu greets me, a strong and stout woman with crinkly eyes that are always smiling. A small crowd of children takes my things and leads me through the warren of thatched huts and dirt paths to our celebration lunch with all the volunteers; we wash our hands with water in tin cans and then gather around large communal bowls. I eat a goat's stomach, wave at the flies, and smile a lot.

The first night I'm exhausted, and by 9 pm I'm splayed under my mosquito net on a scratchy sheet, listening to the sound of a blaring radio, a tribe of crickets that colonize my ceiling, and intermittent donkey brays that pierce through my screen door. My body is drenched in sweat; the air is stagnant and humid. I click on my headlamp and root around until I find my earplugs. These two cylindrical pieces of yellow styrofoam are worth more than the castle of Versailles. I finally fall to sleep.

In the morning Kajatu brings me a bucket of warm water, and I go to the nyegen and bath myself, watching the rain clouds swirling in and listening to the "thunk thunk" rhythm of the women pounding millet throughout the village. The thunks are punctuated by claps, *the women let go of the stick and clap while the stick continues to rise, then they catch the stick again and continue to pound. I am in AWE of this skill and have embarassed myself repeatedly in attempts to acquire it*. I sit in the dirt courtyard between our huts and eat some white bread and drink sugary tea for breakfast, then go to my teacher's hut for my daily routine of Bambara class. The session is soon drowned out by claps of thunder and torrential rain, and we move from our leaky thatched "gwa" (open-sided hangar) to the teacher's bedroom, and continue our lesson sitting on the concrete floor, dimly lit by a small window and a lantern.

For 10 days now I have spent all day learning Bambara, from 8 to 6, with a break in the middle where I go home for lunch. On the way home, I pass a compound where children come streaming out yelling "Bonjore! Bonjore! Bonjore!" and shake my hand, then run to far end and repeat the routine a minute later. It has become an 8-times a day ritual (twice on the way there, twice on the way back, twice on the way there, twice on the way back...). The people of the village are incredibly warm and friendly, and greetings are a very important part of the culture. Each morning I have to greet all the elders in my compound (a family of at least 40 people), inquire about health, how they spent the night, their family, and then give them blessings for the upcoming day. It can be tedious, but I also enjoy the priority of human-to-human engagement. I can't imagine walking down the street in the United States and greeting every person that I pass and asking them if their family is doing well.

One of the hardest things we have learned so far is how to bargain at the market. Last Monday we went to the nearby village and practiced our so-called language "skills." The problem of buying things here is that they refer to FIVE West African Francs as ONE when they tell you the price. Here is a nice example of me buying bananas: (in Bambara)

Me: Hello, how are you? How is your family? How was the night? How are your children?

Seller: Hello, I'm fine. Peace only. Peace only. How are you? How is your family??etc.

Me: Bananas how much?Seller: Bananas twenty twenty.

*oh, they repeat the price? But does this mean 20 bananas for 20? Or a pile for 20? Or 1 for 20? And is the twenty TWENTY, or do I need to times that by 5?*

long pause

Me: Give me 15 bananas.

Seller: hundred two and ten forty

*.... ok, 240, that times 5, ok, that's almost 1000, ok, I'll give him 1000.*

LOTS OF CONFUSION.... finally I walk away with some bananas and possibly the right amount of change. I don't know.

I saw the most beautiful sunset of my life the other night. Two vibrant double rainbows in the East and a molten sky in the West that bathed the earth in yellow light. It was surreal, magical. I spend most evenings sitting in my courtyard while my little brothers watch a Brazilian soap opera dubbed into French, while I study and try to put together basic sentences. I make a fool of myself all the time and get laughed at a lot, but that is part of this process. I like to say very simple descriptive sentences "I am brushing my teeth now with a toothbrush," and when someone understands me it is a big victory for the day.

My host mother Kajatu greets me, a strong and stout woman with crinkly eyes that are always smiling. A small crowd of children takes my things and leads me through the warren of thatched huts and dirt paths to our celebration lunch with all the volunteers; we wash our hands with water in tin cans and then gather around large communal bowls. I eat a goat's stomach, wave at the flies, and smile a lot.

The first night I'm exhausted, and by 9 pm I'm splayed under my mosquito net on a scratchy sheet, listening to the sound of a blaring radio, a tribe of crickets that colonize my ceiling, and intermittent donkey brays that pierce through my screen door. My body is drenched in sweat; the air is stagnant and humid. I click on my headlamp and root around until I find my earplugs. These two cylindrical pieces of yellow styrofoam are worth more than the castle of Versailles. I finally fall to sleep.

In the morning Kajatu brings me a bucket of warm water, and I go to the nyegen and bath myself, watching the rain clouds swirling in and listening to the "thunk thunk" rhythm of the women pounding millet throughout the village. The thunks are punctuated by claps, *the women let go of the stick and clap while the stick continues to rise, then they catch the stick again and continue to pound. I am in AWE of this skill and have embarassed myself repeatedly in attempts to acquire it*. I sit in the dirt courtyard between our huts and eat some white bread and drink sugary tea for breakfast, then go to my teacher's hut for my daily routine of Bambara class. The session is soon drowned out by claps of thunder and torrential rain, and we move from our leaky thatched "gwa" (open-sided hangar) to the teacher's bedroom, and continue our lesson sitting on the concrete floor, dimly lit by a small window and a lantern.

For 10 days now I have spent all day learning Bambara, from 8 to 6, with a break in the middle where I go home for lunch. On the way home, I pass a compound where children come streaming out yelling "Bonjore! Bonjore! Bonjore!" and shake my hand, then run to far end and repeat the routine a minute later. It has become an 8-times a day ritual (twice on the way there, twice on the way back, twice on the way there, twice on the way back...). The people of the village are incredibly warm and friendly, and greetings are a very important part of the culture. Each morning I have to greet all the elders in my compound (a family of at least 40 people), inquire about health, how they spent the night, their family, and then give them blessings for the upcoming day. It can be tedious, but I also enjoy the priority of human-to-human engagement. I can't imagine walking down the street in the United States and greeting every person that I pass and asking them if their family is doing well.

One of the hardest things we have learned so far is how to bargain at the market. Last Monday we went to the nearby village and practiced our so-called language "skills." The problem of buying things here is that they refer to FIVE West African Francs as ONE when they tell you the price. Here is a nice example of me buying bananas: (in Bambara)

Me: Hello, how are you? How is your family? How was the night? How are your children?

Seller: Hello, I'm fine. Peace only. Peace only. How are you? How is your family??etc.

Me: Bananas how much?Seller: Bananas twenty twenty.

*oh, they repeat the price? But does this mean 20 bananas for 20? Or a pile for 20? Or 1 for 20? And is the twenty TWENTY, or do I need to times that by 5?*

long pause

Me: Give me 15 bananas.

Seller: hundred two and ten forty

*.... ok, 240, that times 5, ok, that's almost 1000, ok, I'll give him 1000.*

LOTS OF CONFUSION.... finally I walk away with some bananas and possibly the right amount of change. I don't know.

I saw the most beautiful sunset of my life the other night. Two vibrant double rainbows in the East and a molten sky in the West that bathed the earth in yellow light. It was surreal, magical. I spend most evenings sitting in my courtyard while my little brothers watch a Brazilian soap opera dubbed into French, while I study and try to put together basic sentences. I make a fool of myself all the time and get laughed at a lot, but that is part of this process. I like to say very simple descriptive sentences "I am brushing my teeth now with a toothbrush," and when someone understands me it is a big victory for the day.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)