They showed up in a shining white SUV. We had been waiting for almost two hours, dressed in our matching outfits from last season's village festival, sweat beads rolling down our backs and dripping onto the red dust. When the glimmering vehicle finally rolled up the road, we ran forward, clapping our hands and stomping our feet to the patter of drummers lining the path. The doors opened and three ghostly creatures emerged, two women and a man. Their clothes were crisp khaki (with nifty zip-off legs) and they wore boots and wide-brimmed hats. They were whisked away to the school, and I rode the wave inside a crowd of women, all dressed from head to toe in matching fabric. It was my turn to be in the other end of a village greeting.

When the hubbub had died, the dust had settled, and the figures were finally left alone, I approached, slightly unsure of what to say, of where to begin. They gave a start to see me, a white girl, emerging from the fray of color and sweat and dust. I introduced myself and noted their crisp French accents and pale winter skin. They were astonished to learn that I lived here, that I spoke fluently the local language, that I was going to spend an entire two years in a mud hut. I was astonished that they expected to hop off an airplane from Paris, plop down in a small village, and be able to contribute.

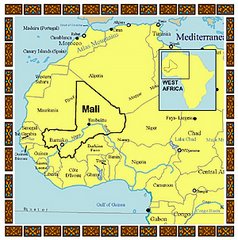

I learned that they had indeed, just gotten off the airplane. This was their first time in Africa, and they were going to spend a week in M'Pedougou in what development workers call "needs assessment." This is where the aid worker ostensibly takes a comprehensive survey of the community and identifies areas of need. Peace Corps volunteers spend more than three months learning about the local customs and values before even beginning to attempt a "needs assessment." But, they were on a limited time frame. They were working for an NGO called Electricians Without Borders and their goal was to see about bringing electricity to M'Pedougou.

The women asked me if I could help organize a meeting with village women, and serve as a translator. I said of course, and two days later we all met under the main thatched shade hut. The meeting progressed through a series of Yes or No questions. "If you were to have electricity, would it help you to study at night?" ...um, Yes. "If you were to have electricity, would it help your children study at night?" ...um, Yes. "If you were to have electricity, would it help you access the outside world through television and radio?" ...um, Yes. One of the women kept nodding and saying "Very good." At this point I suggested maybe they stray from a Yes or No format. She agreed and asked what they did during the day. The women just looked blankly at me, implying, what are these women asking us? I told the French women, "They have no frame of reference. Their daily activities are the norm for them, and they have no idea what you want to know. That they get water at 5am? That they pound millet for hours? That they collect firewood? What do you want and why?" I suggested that she keep it related to electricity, so the women would understand what we were getting at. One of the French women suggested "What if you got a communal television and placed it in the middle of the village, and people could gather in the evenings and watch it together, learning about the outside world?"

I could feel my insides knotting up. Occasionally I have a sensation of floating outside my body and seeing myself from above, and it happened at this moment. I could see my white skin and the white skin of the two French ladies. I could see our crisp manufactured clothing (manufactured by sweatshop labor in some other 3rd world country), my fancy Lexan water bottle, all glittering of money, modernity, and technology in front of this group of rural women. I could see the earnest expressions of good will on our faces, and I thought of the tragic title of a book I read a while back: "Despite Good Intentions." We mean well, but we might actually be doing more harm than good.

(And my knotted up gut spills into my head: A television? First of all, there are already several in the village. For access to the outside world? Have they ever watched television in Mali? If they had, they would know that it consists of nothing but Brazilian soap operas that paint life as a constant drama of sex, infidelity, murder, and money. Intercut with commercials for cars, MSG-laden cooking spices, and cell phones. I thought, wow, they came all this way from France to a village they've never even seen, to bring electricity. Why? Why do we need electricity? How will that help us? They study by lamplight. And watching more television just makes them want things they can't have and don't need.)

The next question was "What do you need?" Ok, this is a bit more open-ended. The answer is "a machine that makes shea butter." Ok. After the meeting one of the French women says to me, "We should look into this shea butter machine. That would be really great to get them one." I just shut my mouth and nod. I'm in no state to speak.

There is, first of all, no way for a small village like M'Pe to create a manufacturing plant, and the machine is expensive, difficult to maintain, and is only profitable at very high volumes. In all of Mali, there are only two. I've been working with the women of M'Pedougou for a year and a half to improve their local production methods in a sustainable manner, and then two French women can hop off a plane and everyone runs for the lure of low-hanging fruit.

I joke with one of my close Malian friends here about our "money trees," because white people are synonymous with money here. It is frustrating, tiring, and depressing all at once. What matters in life are things that our money and technology can not buy. Malians have just about everything that truly matters in life: friendship, family, spare time, food to eat. They lack a few things that we consider pretty important, from the 21st century perspective of the West: clean water, sanitation (every single person lives with amoebas and giardia), dental and health care, and other things like that. What they think they lack, but in fact do not need (in my opinion) are things like motorcycles, pollution, fancy buildings, cars, depression, suicide, homicide, gated communities, and Blackberries. But they see us, they see our TV shows, and they think we're better off, so they want it too.

But we can't all have it. The world is finite, and with almost 7 billion people, I have no idea how we expect to "develop" the "undeveloped" world and continue to maintain our current so-called high standards of living. The average environmental footprint of an American, that is - the resources consumed by an average citizen - if expanded to every citizen of Planet Earth... would require at least 5 or more planets to support the human population. (see redefiningprogress.org)

So there I am, watching the drama unfold in M'Pedougou. Let's help the poor people and bring them machines and electricity and advertisements for consumer goods. That's what we call progress. That's what we call development. I go home and lay in bed that night, wondering if perhaps maybe we've got it all wrong. I've thought this for a long time, but it really starts hitting home when it gets off an SUV and walks right up to my doorstep. We need to be changing the US, not Mali. I guess when I get done with my work here it will be time to go home and get to work on a more monumental task than teaching people about germs and eating beans. I need to teach Americans about riding bicycles, recycling, buying less junk and appreciating friendship over a pot of tea. That would be development.

A few days later the white SUV rolls out of town. They're wonderful people, don't get me wrong. I just wonder if we really know what we're doing.

These photos are taken in Kandiandugu, a neighboring village where a friend of mine works. We went to dance under the giant village tree, escaping the brutal sun but not the heat.

These photos are taken in Kandiandugu, a neighboring village where a friend of mine works. We went to dance under the giant village tree, escaping the brutal sun but not the heat.

Abdouleye, the multi-tasker, hard at work with my home-made bounce board (it bounces light into the faces and illuminates dark skin).

Abdouleye, the multi-tasker, hard at work with my home-made bounce board (it bounces light into the faces and illuminates dark skin). The finished butter, ready to cool into the hardened form.

The finished butter, ready to cool into the hardened form.

I finished filming the first installation of my shea butter movie, and I've started editing. It was a riot to try and get my "actors" to understand why I needed to do multiple takes, why we had to get the kids out of the scene, why they shouldn't look at the camera, etc, etc. It was a lot of fun all the same, and I'm looking forward to showing the finished product.

I finished filming the first installation of my shea butter movie, and I've started editing. It was a riot to try and get my "actors" to understand why I needed to do multiple takes, why we had to get the kids out of the scene, why they shouldn't look at the camera, etc, etc. It was a lot of fun all the same, and I'm looking forward to showing the finished product.