When I see them through the glass at the airport, it really hits me. Eighteen months is a long time. My first glimpse is of my dad’s halo of white hair floating above a see of dark skin in the baggage claim. The halo shimmers like a ghost, prickling my skin with the awareness of passing time. I let my eyes pull focus to my own reflection in the glass, and I study the transparent image fixed in the foreground. My hair is streaked with blond, my arms are less muscular, but I can’t detect any signs of time. Then the halo passes behind my own image, my focus racks back, and I pull in a sharp breath of air. Time passes whether we see it or not, and we are, each of us, just impermanent wisps of life that breathe and live and love and then blow out.

So when the halo comes bursting out of the airport doors I leap from my reverie and go clasp my arms around the very real, the very physical wisp of life in front of me. I hold my dad, my mom, my brother. I look at their faces, and for the first time in 18 months I see a reflection. My brother smiles and I see my own dimples. I think seriously for the first time about what it means to share the same blood. It means a lot.

******

The Lunas stayed for one moon. It was an adventure, a reunion, a recharging, a time of laughter and great learning for all. I remember the first day in Bamako, my dad said, “I just couldn’t imagine it. No matter how many pictures or letters you sent, I just had no idea it was like this.” Yeah. It’s probably dirtier, more polluted, more hectic than I could describe. Alongside women with giant loads of bananas stacked on their heads, herds of goats and cattle weave through the dusty chaos of motorcycles and donkey carts and battered taxis. It’s a hard scene to imagine.

Our welcome in M’Pedougou, my village, was nothing short of spectacular. I called ahead of time to warn of our arrival, and when we pulled up on the road, it was to the sight of 200 people crowded on the roadside. They drummed and sang and did their best to utterly overwhelm the new arrivals. Soon enough the drummers let us unpack and promised that sini, tomorrow, there would be more. Sini, we gathered in the center of village, next to the old mango tree, to dance for hours to balafon music. My mom and dad, who are old-time cloggers, showed off some fancy moves to the delight of the villagers. Each family member was presented with a beautiful bogolan mudcloth, and we received three chickens. The next day my women’s group members came by with a mountain of peanuts. I was taken back with their generosity – their willingness to give the small amount that they have in a gesture of thanks to me and to my family.

The next day, while my brother suffered through a painful (first) bout of giardia, my neighbor Yaya invited us over to weigh his sorghum trial results. Here it was, the final result of the project I’d been working on all year. We had started in March, holding meetings to discuss the scientific research process and to figure out who was doing what, where, and how. I acquired four new varieties of sorghum seed in Bamako at a research station and divvied them up between five farmers. Each farmer was to plant five small plots, one of each new variety and then the local variety as a control. From five farmers, four planted. From four planted, three sprouted (one got eaten by termites). From three sprouted, two survived to maturity (one got eaten by cows). From two mature stands, one got measured (one got damaged by birds). And this was Yaya’s. Yaya, my shining light in M’Pedougou. Yaya only finished fourth grade, but his intelligence, creativity, work ethic, and beaming smile have brought him far in life. Needless to say, I was nervous as we collected the dried up bundles of sorghum and Yaya’s wives started beating the seed off the stalks. I know research is supposed to be “impartial,” but I couldn’t help but hope that all this work might amount to some small opportunity for improvement. The scales gave me an early Christmas gift. The local variety weighed in at 3kg, and one of the new varieties at 5kg, a substantial increase. It was exciting to see positive results, and even better that my dad (himself an agricultural researcher) could be there to see it.

Through the course of our trip, I got to watch my family go through a mini version of the journey I’ve been on for eighteen months. It starts with shock: complete sensory overload. As the shock wears off, it transitions into wonder and excitement, maybe romanticism. As I experienced it, there follows a period of enthusiasm and new ideas, and then as the ideas are suggested and tried and don’t work, or tried and abandoned, or simply not tried, a layer of dust settles on the preliminary enthusiasm. My dad started out full of ideas – like why don’t they have longer handle hoes instead of these short ones that hurt their backs? Answer: they just don’t do it that way. I too started out chock full of ideas, and over time I haven’t lost these ideas, but I have a better idea of why, in fact, things are done the way they are. Tradition. Inertia. Cultural differences. And many reasons that we can’t see at all.

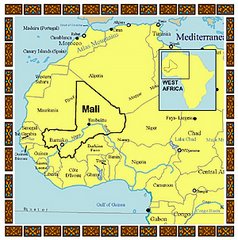

As Americans we are programmed to experiment, to innovate, to improve, to distinguish ourselves. Individuality is prized. Here, people are programmed to do things the way their community has been doing them for a long time. They are taught the values of family cohesion and community. Tasks are accomplished by working together and working hard, and few people stop to think, hey if I did this differently, I could make this task more efficient and potentially reap a greater benefit. Take, for example, the Malian belief that when someone has more than someone else, they should share it. To a Westerner, it means people have no incentive to innovate or do better or work harder because they will just have to give their profit to their family or friends. It sounds like bad capitalism. In Mali, it means that in even one of the poorest countries in the world, very few people are left to fall through the cracks.

As I have gradually become aware of these differences, I haven’t lost “hope,” but I have a greatly altered perspective on development, in particular the pace at which it can and should happen. In my dad’s one month in Mali I saw him jerk through this process of paradigm shifting, wondering why change was so difficult. It would be easy to fall into simple criticism or cynicism or both, but I think the bridge across those two dangerous pits lies in opening the mind beyond culturally programmed beliefs about the way society should work. Recognizing how complicated this puzzle is, I have started letting go of my attempts to “change” people or things. I am not here to force anything on anybody. I’m here to exchange ideas, to give people opportunities if they are interested in them, and to be an American ambassador of peace and friendship.