the ACCRA INTERNATIONAL MARATHON

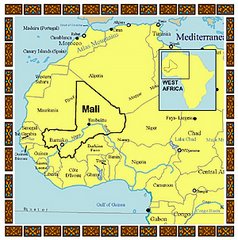

the ACCRA INTERNATIONAL MARATHONWhen my alarm wrenches me from sleep, I lay for a moment relishing the pleasures of a soft bed. What the -- am I doing? On the nightstand is a white square of sheeny paper (like money, it doesn’t tear) with the number 546 on it. I get up, and I’m already dressed: in the one pair of (knee-length-for-modesty) running shorts I came to Africa with, and the pale orange wicking t-shirt that, by the looks of it, won’t be wicking for much longer. I sit in the dark and pull on my grubby running shoes, who also look like relics from war. Why, I ask myself, do human beings, or some of them anyway, choose to engage in activities that they know will be difficult, painful, in fact, down right dreadful? I’m about to run the Accra International Marathon in the capital city of Ghana (south-east of Mali), sandwiched by the Ivory Coast and Togo, and I have to ask myself again what it’s all about.

When I was “training” in Mali, battling bouts of intestinal amoebas (which seem to be a permanent fixture for me), fevers, and herds of cows, I thought about it too. I run in the late afternoon, when the worst of the heat has abated, and people are beginning to come home from the fields. I run out into the ‘bush’ as they call it in French, past fields of corn and sorghum glowing gold, through herds of cows and goats in search of pasture, and … of course, past the people. The women appear as bright splashes of color, their heads loaded with giant baskets or bowls overflowing with the day’s harvest and carefully tied bundles of firewood. From their bright plastic flip flops, to the striped fabric wrapped as for skirts and the equally brilliantly patterned shirts that invariably slip off one shoulder, their bodies glide forward, the necks moving slightly in barely perceptible weaves, left, right, left, right, as they effortlessly balance their loads and chatter and bob their way home. Our paths cross. Their steps are those of exhaustion after a day’s labor, and mine are those of an American in my fancy running shoes, my knees showing, my sunglasses glinting in the sun. We greet and inquire about families, bless the remainder of the day, and continue on. I can’t help but feel a ball of guilt lodge in my throat. Here I am, with such excess energy that I not only can, but I choose, to go running for some ungodly reason. In a place where never-ending back-breaking labor is the norm, the word for happiness or well-being is one and the same as “rest.” Lafine. They don’t need to supplement their lives with extra labor, and they can’t understand why I would choose to do so if I didn’t have to.

So at 3am my friend Bess and I load into a shuttle that will take us to the starting line, 42k, 26.2 miles outside of Accra. There are at least a dozen Peace Corps Volunteers from around West Africa, and we swap stories of training for a marathon in the climactic and nutritional conditions of the Sub-Sahara. We spend at least an hour in the shuttle trying to find the starting place, and when we unload we are alone, until 4:30 when another group arrives. Just as the sky is starting to turn a dark gray purple, someone comes and tells us to walk down the road to the starting line. So the group strings along down the road, everyone muttering about where the start line is, and we walk for what seems like a mile, maybe longer, everyone counting every step as one extra they shouldn’t have had to take in addition to 26.2 miles. Finally a big bus passes us in the opposite direction, filled with neon-green-shirt-wearing runners, and it halts, people get out, and call us back, so we turn around, again, begrudging every step that we walk back, and sit down to wait for the start. An hour and a half later, after more buses full of Ghanians (pronounced Gha- NAY-un) arrive, and the sky has heated up into a milky white soup, the race starts.

Bess and I, both severely undertrained due to illness, allow ourselves a slow start and plod along. The road is a paved country road heading through several smaller towns before passing through the outskirts of Accra and into the city itself. As there are only about 400 runners, the route has not been closed to traffic, so we run in the shoulder. Every so often the race coordinators have put out kilometer markers and they have people in lime green t-shirts handing us bags of water. The sun starts peeking its head out from the clouds, glaring down on us, who are trapped between its angry rays and the smoldering black pavement. Yuck.

At the halfway point I am exhausted, just boiling hot and my knees are telling me that my running shoes are what they look like: junk. I pass “21 km” and my heart plummets. There is no way I can do this. And, as if by magic, the sun’s anger ebbs and it agrees to slink back into the clouds. I grab a bag of water, break it onto my head, and just then the road turns a corner and the Atlantic Ocean spills out in front of me, deep blue with little white diamonds dancing across its surface. Ok. I’ll just go slowly.

The runners are, at this point, spread out, and Bess and I have separated. There is no one around, so it is just me and the ocean. When the road finally turns back inland, I thank the waves for their moral support and steel myself for the final legs. The last 15k run through the outlying areas of Accra, and for one long, interminable stretch of road, I dodge public transport buses, taxis, push carts, women with heads stacked high, dogs, and bicycles. The shoulder devolves into a slanting patch of dirt. I’m getting thirsty, it’s been a long time since I have seen a race vehicle. I look as far as I can behind me and ahead of me, and I see no bright lime green. Oh no, what if I missed a turn and I’m just running off into some market of the sprawling mass of Accra? I stop and ask someone if they have seen runners go by. They say yes, and I heave a sigh of relief. Twenty six miles is long enough, I don’t need to get lost.

It was as much suffering as I could have hoped for, and I felt glad when it was all over. I don’t know what I learned or gained from the experience. That I can make myself suffer? One aspect that always intrigues me is the mental side: the power that your mind has to determine your perspective. My body may be suffering, but I can choose to look at the waves crashing on the beach and just recognize the pain, be with it, and not do what humans always try to do: get rid of it. When we can be with suffering, understand it, not run away from it, then perhaps it loses its power over us. I remember at one point passing a runner and commenting on a funny billboard in front of us, and he gave me a sigh, (how can you be thinking about a funny billboard when we are suffering like this??). It’s all relative.

---------------

Speaking of relativity, our trip to Ghana was eye-opening. We traveled overland the thousand+ miles, going through Burkina Faso and moving gradually from the dry sahel to the lush sub tropics. We also noticed a gradual shift, from Islam to Christian, from Bambara to French and Mossi, to Twi and English. The first time we got out of a bus in Ghana, at a legitimate “bus stop,” our jaws dropped. Pavement, everywhere. Trash cans. Ice cream sellers. General cleanliness and orderliness the likes of we haven’t seen for awhile. I wondered what my impression of Ghana would have been had I come directly from the States or Europe. My relative perspective was that Ghana was the promised land. When we left Ghana we were flat broke, scrounging our last coins and made the journey up to Burkina with just enough money to pay for the use of public drop latrines and the occasional bag of filtered water. We spent a night on benches at the Ghana/Burkina border before it opened the next morning, and then we gradually transitioned back into the Africa we are used to: inconsistent transport, swelteringly hot, and no ice cream on carts. We spent the last night of our trip wrapped in a mosquito net in Bobo-Dioulasso, waiting for the bus that never left (they said 10pm, we left at 5am). My friend Sarah asked me, “Jessie, when will it no longer be ok to be sleeping on the ground in dirty bus stations with overflowing latrines?” I couldn’t answer. I don’t know. For now it’s an adventure.

Speaking of relativity, our trip to Ghana was eye-opening. We traveled overland the thousand+ miles, going through Burkina Faso and moving gradually from the dry sahel to the lush sub tropics. We also noticed a gradual shift, from Islam to Christian, from Bambara to French and Mossi, to Twi and English. The first time we got out of a bus in Ghana, at a legitimate “bus stop,” our jaws dropped. Pavement, everywhere. Trash cans. Ice cream sellers. General cleanliness and orderliness the likes of we haven’t seen for awhile. I wondered what my impression of Ghana would have been had I come directly from the States or Europe. My relative perspective was that Ghana was the promised land. When we left Ghana we were flat broke, scrounging our last coins and made the journey up to Burkina with just enough money to pay for the use of public drop latrines and the occasional bag of filtered water. We spent a night on benches at the Ghana/Burkina border before it opened the next morning, and then we gradually transitioned back into the Africa we are used to: inconsistent transport, swelteringly hot, and no ice cream on carts. We spent the last night of our trip wrapped in a mosquito net in Bobo-Dioulasso, waiting for the bus that never left (they said 10pm, we left at 5am). My friend Sarah asked me, “Jessie, when will it no longer be ok to be sleeping on the ground in dirty bus stations with overflowing latrines?” I couldn’t answer. I don’t know. For now it’s an adventure.

HOSPITALITY

It’s becoming almost a ritual for us now- every Monday morning Abdouleye and I pack up our materials and head out to a neighboring village to do our shea nut trainings. This past Monday we went to a village for a second training session.

I show up at Abdouleye’s hut on the roadside around 8, and he isn’t there. I sit down under the big mango tree, already seeking shade from the brutal sun, and watch donkey carts bumping past on their way to the fields. Abdouleye comes up the road, and we greet. Then he says “Sita, my bike is broken. The frame itself has snapped,” and he shows me his bicycle, a patchwork of teal and light blue and rusted metal. Indeed, the frame is broken. “I’ll get one to borrow,” and he disappears again, then comes back after a bit with another bike. We load up and set off.

The path to Zhiworodougou winds its way back from the road for some 10k. We pass through fields of towering sorghum, sweet potatos, people picking peanuts, thrashing rice. We dip through mango groves and weave through small gatherings of huts that are invisible until the very moment you reach them because of the sorghum. By the time we reach Zhiworodougou we are both drenched in sweat. We dismount and pull our bikes into the shade. A woman in blue and white fabric greets us and comes towards me, dipping down to her knees. How are you? How is M’Pedougou? How is your family? How are your work partners? Did you arrive safely? Welcome. I awkwardly respond. I’m fine with the Senoufo, it’s the kneeling thing I’m still not comfortable with. Women don’t kneel to other women, they only kneel to men. I’m an honorary man here, but it makes me feel uneasy to be in such an unbalance of power.

I hear the ringing from a distance – they have struck the metal gong that serves as an effective telephone tree “Meeting! Meeting!” and Abdouleye and I are guided through the village, past the chief’s house to greet, where he gives us a bag of peanuts and blesses us for several minutes. It is fully 11am by the time we sit down in the meeting hut. The sun is melting my skin off and the respite of shade is diminished by the oppression of 70 bodies crammed into a small mud building. Our host, Adama, puts two chairs out, and no sooner have we sat down then another man walks in with more chairs and insists that I move into the more comfortable chair. Fine. Anything to make sure the white girl is as comfortable as possible. Adama sits by the door and before I can blink he begins tending to a small stove and pours loose-leaf black tea into a teapot.

The meeting starts and I greet, bless, then turn it all over to Abdouleye. We have a picture series depicting the steps of shea nut and butter production, and he goes through them one by one, explaining, answering questions and quelling debates. There are at least 60 women, and behind us sit about 10 older men, seated around on a low mud bench. Beside me, Adama is pouring tea back and forth from the teapot to a shot glass, from shot glass to tea pot, and then he adds another shot glass worth of sugar. He interrupts loudly, “Sita,” to give me the first shot of tea, and I take it with my right hand (supporting it with my left to show deference) and I drink the tea somewhat guiltily, seated in front of a crowd of women (women rarely get to drink tea), and hand the glass back.

I flash back to my very first day of homestay, only a week after arriving in Mali, when the village greeted us with a ceremony and gave each volunteer a cold Coke in a glass bottle. Coke wasn’t sold in that village. Someone had had to go on a motorcycle to buy the drinks and bring them specially for us. I remember sitting guiltily in front of the villagers, drinking a cold soda that I didn’t even want.

The session takes a few hours, and when Abdouleye finishes I’m as drenched in sweat as when I arrived in Zhiworodougou. I think we’re done. But oh, there’s more talking. Abdouleye says something (this is all in Senoufo, I only catch pieces) to Adama, and then I notice that Adama turns to the man next to him and says, Sedu, did you hear what Abdouleye said? And he repeats what he heard. And then Sedu turns and repeats what he heard, around like that. I ogle. That’s why our meeting had been taking so long. Then a woman comes forward with two large bowls. “Sita, you came here once before and told us about these new shea butter techniques. We heard what you said and we did what you told us. Here.” She opens the bowls to reveal one bowl containing a yellow ball that looked like soft margarine, the other filled with a hard off white substance with a soft sheen. The women gather excitedly behind her, “Ok, now which one was dried in the sun and which one was smoked over a fire?” I laugh and clap my hands for the women, and I point to the clean white bowl and say “sun –dried.” The women erupt in clapping and that’s that.

We are presented with a giant bag of sweet potatoes, more bags of peanuts and a chicken, and we are ushered out to lounge in the shade and enjoy another round of tea while we wait for the heat to fizzle out a bit. Around 4, we strap our gifts on the backs of our bicycles. The chicken’s legs are tied and she dangles awkwardly upside down from Abdouleye’s handlebars. He pulls on his 2008 brand sunglasses (the zeroes are little soccer balls), and we are escorted to the edge of the village. I thank them for their gifts, and for their work, and as they hold my bicycle and take turns shaking my hand, wishing me a safe return, I feel the true meaning of hospitality.

We are presented with a giant bag of sweet potatoes, more bags of peanuts and a chicken, and we are ushered out to lounge in the shade and enjoy another round of tea while we wait for the heat to fizzle out a bit. Around 4, we strap our gifts on the backs of our bicycles. The chicken’s legs are tied and she dangles awkwardly upside down from Abdouleye’s handlebars. He pulls on his 2008 brand sunglasses (the zeroes are little soccer balls), and we are escorted to the edge of the village. I thank them for their gifts, and for their work, and as they hold my bicycle and take turns shaking my hand, wishing me a safe return, I feel the true meaning of hospitality.

Some are lucky enough to have cows, and the men till the fields with cow plows before seeding, but others just hack at the dry crusted earth with their sculpted, weathered muscles, and little by little they plant hectare after hectare of peanuts, rice, sorghum, millet, and corn. Once the seed is in the ground, the first field is already weed-infested, and the frenzy of weeding begins. It is truly back-breaking labor, and I marvel at how they tackle such a seemingly hopeless task(eleven hectares of corn stretches for a loooong way).

Some are lucky enough to have cows, and the men till the fields with cow plows before seeding, but others just hack at the dry crusted earth with their sculpted, weathered muscles, and little by little they plant hectare after hectare of peanuts, rice, sorghum, millet, and corn. Once the seed is in the ground, the first field is already weed-infested, and the frenzy of weeding begins. It is truly back-breaking labor, and I marvel at how they tackle such a seemingly hopeless task(eleven hectares of corn stretches for a loooong way). Last week my host dad 'hired' the women's group of my family (the Bengali women) to come weed his field for a day - 40 women for an entire day for about 10 US dollars. Wow. The old women came with their 'chichira' shaker gourds and sang, and women would rise to dance and sing as they hoed, drenched in dirt and sweat. Abdouleye told me that when he was a kid it was always like that, that when people went to plant, the drums came too, and their was dancing and singing in order to urge people along in their work. But, he says, the cow plow came and it is hard to play drums, and that the tradition has mostly disapeared. I can't help but question what constitutes progress Yes, the cow plow is good, I won't deny that, but it saddens me to see how quickly their society is being overtaken by new technology - at such a speed that they don't have time to adjust their cultural practices... they just get lost.

Last week my host dad 'hired' the women's group of my family (the Bengali women) to come weed his field for a day - 40 women for an entire day for about 10 US dollars. Wow. The old women came with their 'chichira' shaker gourds and sang, and women would rise to dance and sing as they hoed, drenched in dirt and sweat. Abdouleye told me that when he was a kid it was always like that, that when people went to plant, the drums came too, and their was dancing and singing in order to urge people along in their work. But, he says, the cow plow came and it is hard to play drums, and that the tradition has mostly disapeared. I can't help but question what constitutes progress Yes, the cow plow is good, I won't deny that, but it saddens me to see how quickly their society is being overtaken by new technology - at such a speed that they don't have time to adjust their cultural practices... they just get lost.

And MORE pictures are at

And MORE pictures are at

We don't spend long before the instruments are hoisted up again. There are still hordes of new musicians and dancers arriving, but we're the first wave, so we move out through the forest, traipsing across dried out crop fields, picking over millet and sorghum stalks. We pass by the giant tree, give it our blessings, and move into the fields to dance.

We don't spend long before the instruments are hoisted up again. There are still hordes of new musicians and dancers arriving, but we're the first wave, so we move out through the forest, traipsing across dried out crop fields, picking over millet and sorghum stalks. We pass by the giant tree, give it our blessings, and move into the fields to dance.

Soon a child came and asked to speak to Abdouleye. He went out and came back, “Sita, let’s go home.” I looked at him curiously, wondering why he wanted to go, and of all things, home. We started walking and he said, “My mother, she’s passed away.” I nodded and as we walked I quietly gave him my blessings (Bambara fills that gap we have in English – that awkward sticky feeling of oh gosh, I want to console you, but I don’t know what to say… Um, I’m sorry? In Bambara there is a string of ‘death blessings’ that smooth over that gap. May Allah return her to the Earth. May he cool her resting place. May her children live out the life that she gave them) At his mom’s hut, the family was beginning to gather, trickling in from marriage festivities, their gaiety muffled. Abdouleye’s brother was sitting on a carved wood stool sobbing, tears making dark lines on his dusty cheeks. Their older brother, my language tutor Adama, drunk on millet beer from the marriage festivities, was preaching to no one in particular about the naturalness of death. The women began to gather and the singing began that afternoon.

Soon a child came and asked to speak to Abdouleye. He went out and came back, “Sita, let’s go home.” I looked at him curiously, wondering why he wanted to go, and of all things, home. We started walking and he said, “My mother, she’s passed away.” I nodded and as we walked I quietly gave him my blessings (Bambara fills that gap we have in English – that awkward sticky feeling of oh gosh, I want to console you, but I don’t know what to say… Um, I’m sorry? In Bambara there is a string of ‘death blessings’ that smooth over that gap. May Allah return her to the Earth. May he cool her resting place. May her children live out the life that she gave them) At his mom’s hut, the family was beginning to gather, trickling in from marriage festivities, their gaiety muffled. Abdouleye’s brother was sitting on a carved wood stool sobbing, tears making dark lines on his dusty cheeks. Their older brother, my language tutor Adama, drunk on millet beer from the marriage festivities, was preaching to no one in particular about the naturalness of death. The women began to gather and the singing began that afternoon.

After a nice birthday dinner of toh and okra sauce, I head home, and hang up a lantern from my straw-covered hangar. Abdouleye, Yaya, Daouda and Baba come over and we make tea and chat until our eyelids droop and the milky way has crept up from the Southern horizon. I climb into the safe womb of my mosquito net and try not to think about the sweat already trickling onto my sheet.

After a nice birthday dinner of toh and okra sauce, I head home, and hang up a lantern from my straw-covered hangar. Abdouleye, Yaya, Daouda and Baba come over and we make tea and chat until our eyelids droop and the milky way has crept up from the Southern horizon. I climb into the safe womb of my mosquito net and try not to think about the sweat already trickling onto my sheet.

Feb. 7

Feb. 7